Persepolis

“Takht-e Jamshid” or as it is called by the Greeks “Persepolis” is the name of one of the Iranians ancient cities. “City of Persians” or “Parsa” known to the ancient world as “The wealthiest city under the sun” was a ceremonial capital of the second Iranian dynasty, the Achaemenid Empire.

The construction of this capital began in 515-518 BCE by the King Darius the Great and was continued during the reign of his son, King Xerxes the Great and grandson King Artaxerxes I in an area of 125,000 square feet and was prosperous for about 200 years. It is also estimated that this construction with about 39 building had around 43600 residents.

Alexander the Great and the Greek army attacked Iran in 330 BCE and burned down the Persepolis and destroyed a vast number of books, culture and arts of the Achaemenid. At the moment the magnificent ruin of Persepolis is an archaeological site located in southern Iran (situated about 70 km northeast of the modern city of Shiraz in the Fars Province) and is one of the most artifact-rich archaeological sites in the world, called by UNESCO as a world heritage site.

Panorama of ruin of Persepolis

This city was built as the most magnificent of the four Achaemenid capitals — Susa, Ecbatana, Persepolis and Babylon — which were founded in logistic locations to help Achaemenid kings efficiently administer their vast empire (The Achaemenid Persian empire was the largest that the ancient world had seen, extending from Anatolia and Egypt across western Asia to northern India and Central Asia). Persepolis is believed to be constructed to be a majestic atmosphere, a place to celebrate events, a symbol of the Achaemenid Empire and an example of the dynastic city, and that is why it was destroyed and burned by Alexander the Great in 330 BCE (the historian Plutarch claimed that the Greeks carried away the treasures of Parsa on the backs of 20,000 mules and 5,000 camels).

Persepolis: In the forefront – Garrisons Quarters, the Hall of Hundred Columns and further Apadana

This Achaemenid capital was known for its stunning inscriptions, unique architecture and wooden columns made of tall Lebanese cedars and Indian teak trees. Persepolis was built in terraces up from the river Pulwar to rise on a larger terrace, partly cut out of the Mountain Kuh-e Rahmet (“the Mountain of Mercy”). Major tunnels for sewage were dug underground through the rock and a complex system of water channels and drainage was cut into the rocky terrace. The palaces were then built on the terraces. One of the architectural arts in Persepolis is the ratio of the height to the width of the doors and also the ratio of height of the columns to the distance between two columns is a golden ratio (In Geometry, two quantities are in the golden ratio if their ratio is the same as the ratio of their sum to the larger of the two quantities).

The terrace, seen from the southeast

A water conduct

Statue of mythological creature “Griffin” or “Homa” (bird of happiness) at entrance gate

The large column bases and capitals of the palaces were made of limestone of various colors and monolithic blocks of Stone were used to make the porticos, stairs, corridors and many of the window frames. No mortar was used between the stone blocks and many of them were joined by iron clamps and molten lead. the two surface stuck on each other were carved in a way that they were so smooth that respectably mounted on one another. Joint operation was done in several ways, one is lock and pair, where a part of the stone is highlighted, and a same size hole is made on the other stone and the two stones were locked on each other. However the most frequent method was digging two identical holes in two adjacent stones and by using metal clamps they were connected to each other and then melted lead was poured on it and then polished.

Using metal clamps instead of mortar for hammering stones

Over time Persepolis has seen earthquakes but the columns of the palaces have remained standing through them all. At first glance the columns seem one piece but in fact they are made out of different pieces assembled on each other. The secret of their stability against earthquakes is at their junction point, where two stones are connected by a molten lead. This lead along with tightening the two connected pieces plays an important role for structural strength against earthquakes. Lead is a soft, ductile metal that reacts when an earthquake occurs and does not crack. This is the same role that in modern buildings the spring placed between the columns performs.

More than 3,000 designs decorate the buildings and tombs of Persepolis. Although these designs are numerous, they are amazingly similar .The individual figures of soldiers aligned along the stairways and walls are repeated hundreds of times with only minor variations. Persians, Medes and most foreigners are portrayed with identical faces. Their heads and feet are invariably depicted in profile. The Persians wear long creased robes and are shown in a limited number of representations, whereas the Medes are all shown wearing knee-high garments with short sleeves.

Median (left) and Persian (right) soldiers, carvings at Persepolis

A view of a column in the Hundred Columns Palace at Persepolis

A Persepolis Relief in British museum

Every year on March 21st, the representatives of the different Satrapies (governorships) established by Darius came to Persepolis to celebrate the Persian New Year, Nowruz, and present the king with their finest gifts. Persepolis carvings show Bactrians, Babylonians, Phoenicians, Ethiopians, Indians and Arachosians carrying gifts as valuable as gold and ivory.

Delegates offer tribute to the Persian king

Relief sculpture in Persepolis stairs

Detail of a relief of the eastern stairs of the Apadana at Persepolis

All available evidence shows that Persepolis has served dual but related purposes. Firstly, being the seat of the government, it constituted an appropriate treasury for the ever-increasing Wealth of the country and secondly, it was a befittingly majestic locale for the grandiose ceremonies wherein the Iranian emperor received in audience the heads of state and representatives of the 28 countries under his dominion. Every year, the grand festivities of Nowruz were held in Persepolis and, upon the orders of Darius the Great, astronomers prepared a very precise calendar that is still in existence on the basis of which the first day of the year coincided exactly with the first day of spring. Architects, artists and professionals involved in constructing the Persepolis came from the cities under Achaemenid Empire.

Below you can see the architectural plan of Persepolis Covering an area of over 125,000 square meters:

The buildings at Persepolis include three general groupings: military quarters, the treasury, and the reception halls and occasional houses for the King. Noted structures include:

The Great Stairway (The Grand Entry: Dual entrance to the Palace)

The Great Stairway of Persepolis is a 14-meter-high double-return stairway, 111 wide and short steps (height 10 cm) from each side, which was designed in such a way that one could only proceed slowly and with dignity, because you are forced to walk upright. Historians claim that the stairs are made this way so that horses are also able to climb the stairs, but the real reason is that stairs are made shorter than usual, so that comfort and magnificence of the Guests (whose images with fine and long clothes are carved on the walls of Persepolis) is preserved when climbing them. The Guests were led by a Persian or a Median noble through these stairs.

Persepolis was built on vast artificial platform. Therefore, the entrance in ruins climbs the stairs of 111 steps

Entrance stairway of persepolis

The Gate of all Nations (Gateway to all Nations and the entrance into the ancient city of Persepolis)

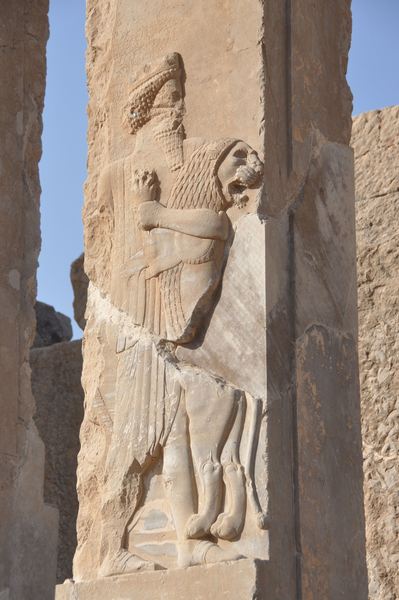

The Gate of all Nations, referring to subject nations of the empire, consisted of a grand hall that was a square of approximately 25 meters (82 ft) in length, with four columns and its entrance on the Western Wall. There were two more doors, one to the south which opened to the Apadana courtyard and the other opened onto a long road to the east (the Processional Way). All people from all subject nations had to go through this gate to enter the palace complex. While Persians and Medes had the privilege to take the south door directly towards Apadana, all the other subject nations were supposed to use the eastern door to the Processional Way to approach the Throne Hall. A pair of Lamassus, bulls with the heads of bearded men, stood by the western threshold. Another pair, with wings and a Persian head stood by the eastern entrance, to reflect the Empire’s power. To the left of the gate, the Apadana courtyard & its northern stairs are located.

The Gate of all nations, the symbols of Persepolis appears when climbing the large stairs.

The Gate of all Nations (eastern entrance)

The Gate of all Nations (western entrance)

The Apadana Palace

The Apadana Palace, the greatest of all palaces in Persepolis, was built by Darius the Great. The palace had a grand hall in the shape of a square, each side 60 meters (200 ft) long with seventy-two columns. Thirteen of which still stand on the enormous platform, each column is 20 meters (62 ft) high with a square Taurus and base. At the western, northern and eastern sides of the palace there were three rectangular entrances each of which had twelve columns in two rows of six. Two grand symmetrical stairways were built and four towers were built in the four corners of the palace, facing outwards. The façade of the relief-decorated palace was decorated with images of the King’s best guards known as the Immortals. They are ready for battle, carrying a sword, spear, and shield. Above them is a traditional representation of a winged sun, flanked by two sphinxes.

A view of Apadana Palace

Members of the Persian Imperial Guard

The eastern stairs of the Apadana palace, with exquisite stone relief, miraculously survived the sack of Persepolis by the soldiers of Alexander the Great. The relief consists of three parts: the northern wall, with representations of Achaemenid dignitaries; the center, with eight soldiers; and the southern wall, showing a procession of people from different subject nations bringing tribute to the Achaemenid king, Darius the Great. Dignitaries, who entered the great hall, sat on black marble benches waiting their turn to pay homage to the king. While military officials passed through the eastern gate toward the Hundred-Columns Palace, gift-carrying mandarins were guided toward the Apadana Palace, also known as the Royal Audience Hall. The Audience Hall was covered by multi-colored carpets and its walls were beautifully decorated with tiles and various forms of ornamentations.

Stairway of Apadana Palace, some of the best preserved elements of Persepolis

Stairway of Apadana Palace, some of the best preserved elements of Persepolis

Relief at the base of the Palace of Darius

Apadana palace has two sets of stairs in the North and East.

Eastern stairs of the palace with two staircases – one facing north and one facing south – is composed of carved designs on their side wall. Northern stairway is designed with the Medo-Persian commanders, while holding lotus flowers in their hands. In front of the military commanders, the Immortal Guards are seen making a tribute. In the upper row of the wall, you can see people holding gifts and walking towards the palace. Southern staircase shows images of representatives of different countries holding gifts. Each section of this stairway is dedicated to one of the nations, as specified in the following figure:

- Median 2. Elamite 3. Parthians 4. Scythians 5. Egyptians 6. Bactrians 7. Scythians 8. Armenian 9. Babylonians 10. Cilicians 11. Sakaians (Sakā tigraxaudā) 12. Ionians 13. Samarkand residents 14. Phoenicians 15. Cappadocians 16. Lydian’s 17. Arachosians 18. Indians 19. Macedoniana 20. Arabs 21. Assyrians 22. Libya 23. Ethiopians

Stairway of Apadana Palace, reliefs of representatives of different countries

Stairway of Apadana, Darius and Xerxes Receiving Tribute

Stairway of Apadana, Assyrians with Rams

The Hall of a Hundred Columns (The Throne Hall: Imperial Army’s hall of honor)

The Throne Hall or the Hundred-Columns Palace was built by Xerexes and completed by his son Artaxerxes I at the turn of the fifth century BCE. The columns were made of black marble with double-headed bull capitals.

Bull capital, from a pillar at Hundred-Columns Palace

Plans and details of the columns of Persepolis

The monument had eight stone doorways bearing images of the throne and the king. The Throne Hall is the second largest building at Persepolis (70×70 square meters). It had 100 columns supporting the roof. In the beginning of Xerxes’s reign, the Throne Hall was used mainly for receptions for military commanders and representatives of all the subject nations of the empire. Later the Throne Hall served as an imperial museum/treasury as the gold and other treasures had grown so much that the original treasury’s space had not been enough and part of the treasures were moved and kept here. Through the gate the Harem’s building can be seen with a bull capital in front of its entrance. It is used as a museum today.

Hall of Hundred Columns

Two massive bulls guarded the hall entrance, one of which (undamaged) is now in Chicago’s Oriental Institute. The Bull gate of the Hall of 100 columns is located in the courtyard between the unfinished gate at the end of the Processional Way and the Hall of 100 Columns (The Throne Hall). The Main Entrance of the Throne Hall had a portico decorated with two colossal bulls. The entrance itself is decorated with 5 rows of Persian and Mede soldiers and on the sixth row the king on the throne in audience. The south Entrance of the Throne Hall is decorated with 3 rows of people from different nations carrying the king sitting on his throne over their heads in the highest row, showing the position of the king and all the other nations in the empire.

A bull at the northern gate of the Hall of Hundred Columns

The entrances to the Hall of Hundred Columns

Reliefs of 100 people, at the south entrance of the Hall of Hundred Columns

The Tripylon Hall

The Tripylon (triple gate) Palace of Persepolis can be found between the Apadana and the Hall of Hundred Columns. To the north of the building is a flight of stairs, decorated with guardsmen. The Tripylon Palace or the Council Hall was used by Achaemenid kings to hold council with high-ranking Persian and Median noblemen and officials. This palace is one of the smaller palaces comparing to the other palaces but it serves a great duty. The middle of the main room, by precise calculation is the geometric center of Persepolis platform; hence it is called the Central palace.

Stairway platform of Tripylon Palace

Entrance gates of Tripylon Palace

Tachara Palace of Darius “winter palace” or the Hall of Mirrors

This palace was one of the few structures that escaped destruction in the burning of the complex by Alexander. The Tachara, measuring 1,160 square meters (12,486 sq. feet), is the smallest of the palace buildings in Persepolis. Its main room is a mere 15.15m x 15.42 m (49.70 ft. x 50.59 ft.) with three rows of four columns. Darius built Tachara or the Hall of Mirrors as his private palace. The hall was covered with polished stones that reflected images when sunlight shone through the windows.

The palace, seen from the south

The Royal Warrior

Northern entrance

The Hadish Palace of Xerxes

This palace is north of Xerxes Palace (Hadish) in an area between Xerxes and Darius Palace, but also between Apadana and Tripylon.

The Hadish was king Xerxes’ personal palace. Spanning an area of 2,250 square meters, Hadish was the first palace Alexander set fire to and is therefore the palace which sustained the most damage. On the southern side of Hadish stood the Queen’s Palace where the royal ladies resided. Its western wing, reconstructed in the 1930s, now houses the Persepolis museum.

The ruins of the Hadish palace

Relief of the great king leaving the palace

The Imperial Treasury

The Imperial Treasury was one of the first buildings constructed in Persepolis, described by many historians as a land of riches. A great part of the building was ruined and its riches were looted when Alexander’s army set fire to the great capital in 330 BCE, wiping all traces of its two centuries of beauty and splendor.

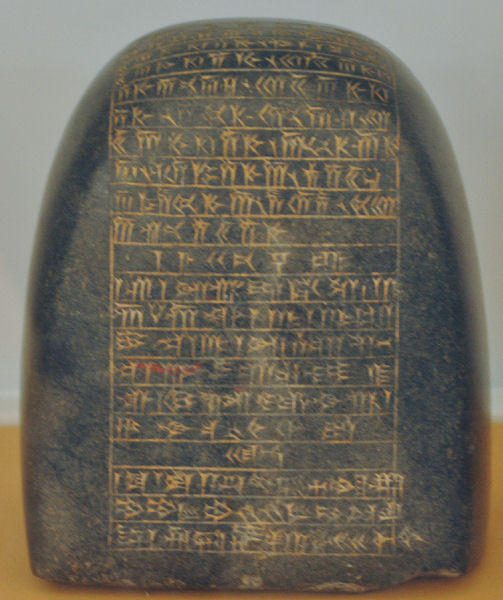

Among the few recovered objects from the treasury are a number of clay tablets, which provide valuable information about Persepolis workers. These Elamite inscriptions show Persepolis workers were not slaves and were paid for their labor. They also show that Persepolis workers had female supervisors called chiefs, who were sometimes paid twice as much as men and received special maternity benefits.

View of the ruin of the Imperial Treasury

The weight known as DWc

Unfinished Gate

Construction of the Unfinished Gate of was probably started by king Artaxerxes III , and ought to have been continued by his successors. However, there was a civil war going on, and later, the Macedonians invaded the Achaemenid empire. This probably explains why the monument was never finished. If it had been completed, visitors would have entered Persepolis through the Gate of All Nations, would have proceeded through the Army Road, crossed this gate, and had reached the Hall of hundred columns. However, the monument was still unfinished when the Alexander captured Persepolis. Today, hardly anything survives, except for one pair of unfinished lamassu ‘s in the south (a lamassu is a bull with the head of a bearded man).

Pair of unfinished lamassus at the unfinished gate

Queen’s Quarters

The “Queen’s Quarters” or “harem” is the name of several buildings in the southeastern part of the Persepolis. One of these buildings is now in use as a museum, and as the office of the Persepolis archaeological complex.

The name “harem” is perhaps better avoided. It should be stressed that Achaemenid harems never existed and are in fact an invention by western scholars. The decoration of the Queen’s Quarters is not very different from the rooms of the king – reliefs of royal warriors fighting against lions and so on.

The northern portico of the Queen’s Quarters: now a museum

The northern portico of the Queen’s Quarters: now a museum

Hall of 32 Columns, the Royal Stables, and the Chariot House are other constructions in this capital.

The Tombs of Kings

About 6 kilometers northwest of Persepolis lay the imposing site of “Naqsh-i-Rustam” in the mountain range of “Husain Kuh”, where Darius the Great and his successors had their monumental tombs carved into the cliff. There are four tombs belonging to Darius I the Great, Xerxes, Artaxerxes I, and Darius II.

As is customary, the relief on the upper part of the tomb shows the king sacrificing to the eternal, sacred fire and the supreme god Ahuramazda. He is standing on a platform that is carried by people that represent the subject nations.

Although Naqsh-i-Rustam had long been a sacred area (as the remains of a Pre-Achaemenid relief show), Darius the Great was the first to choose it as a burial place. His successors not only imitated his idea of a cliff tomb but also copied the layout of the tomb itself. The dramatic facade of the tomb is constructed like a cross. An entrance leads into the tomb chamber, cut deep into the rock. In the panel above this facade is a relief depicting the king standing on a three-stepped pedestal in front of an altar. His hand is raised in a gesture of worship. Above him floats the winged disk of Ahuramazda, god of the Zoroastrian religion. This scene is supported by throne bearers representing the twenty-eight nations of the empire. On the side panels are the king’s weapon bearers and the Persian guards. The trilingual cuneiform inscriptions on three panels of the rock wall either enumerate the twenty-eight nations upholding the throne or glorify the king and his rule. Some traces of pigment found on the facade of the royal tombs suggest that all or most of the stone reliefs had been painted.

Panorama of Naqsh-e Rustam. The order of the tombs in Naqshe-e Rustam, from left to right: Darius II, Artaxerxes I, Darius I and Xerxes

Map:

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Persepolis

http://www.persepolis.nu/persepolis.htm

http://www.livius.org/pen-pg/persepolis/persepolis.html

http://www.ancient.eu/persepolis/

http://9.pro.tok2.com/~yucky/english-iran-ryokou-peruseporis.html

http://www.persepolis3d.com/frameset.html

http://www.arianica.com/en

http://shiraztourism.ir/persepolis-movies/

http://www.stockholm360.net/list.php?id=persepolis

http://www.irpedia.com/iran/best/1931/

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/persepolis

http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Persepolis

https://oi.uchicago.edu/collections/photographic-archives/persepolis/royal-tombs-and-other-monuments

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/acha/hd_acha.htm

http://www.ancient.eu/Achaemenid_Empire/

http://www.trekearth.com/gallery/Middle_East/Iran/East/Fars/Persepolis/page1.htm

http://www.bible-history.com/archaeology/persia/darius-seated.html

http://www.artarena.force9.co.uk/persep1.htm

http://www.farschto.ir/en/encontent/tourisme/takhtejamshid.html

https://fa.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D8%AA%D8%AE%D8%AA_%D8%AC%D9%85%D8%B4%DB%8C%D8%AF#.D9.86.D8.B8.D8.A7.D9.85_.D9.BE.D8.B1.D8.AF.D8.A7.D8.AE.D8.AA_.D8.AD.D9.82.D9.88.D9.82_.D8.A8.D9.87_.DA.A9.D8.A7.D8.B1.DA.AF.D8.B1.D8.A7.D9.86_.D8.AA.D8.AE.D8.AA_.D8.AC.D9.85.D8.B4.DB.8C.D8.AF

http://www.beytoote.com/iran/bastani/persepolis-tahktejamshid.html

http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/114

http://www.anobanini.ir/travel/fa/fars/1385/10/post_19.php

http://www.shegeftiha.com/946-%D8%B4%DA%AF%D9%81%D8%AA%DB%8C-%D9%87%D8%A7%DB%8C-%D8%AA%D8%AE%D8%AA-%D8%AC%D9%85%D8%B4%DB%8C%D8%AF/

http://daneshnameh.roshd.ir/mavara/mavara-index.php?page=%D8%AA%D8%AE%D8%AA+%D8%AC%D9%85%D8%B4%DB%8C%D8%AF&SSOReturnPage=Check&Rand=0

D5 Creation

D5 Creation